Practice Buddy

I played piano growing up but never got exceptionally good. Like many people, I stopped almost altogether after college and now, when I do play, it’s primarily just speeding through old pieces I used to know rather than undertaking the serious endeavor of practicing. By this I mean I spend no time warming up, improving technique, learning new music, memorizing, or otherwise furthering my ability

Honestly it’s embarrassing because I cant demonstrate how sick and talented I am to new people I meet and, now that I have a keyboard in my apartment, there will be pressure to play when people come over.

Recently, my girlfriend got me the music for Ravel’s Un Barque Sur L'Ocean and asked me to learn it. I’ll say two things right off the bat — first she had dramatically overestimated my ability and the alacritiy with which I learn new music. Second, I am only now, as I look up the spelling for this post, realizing that it was heavily featured in Call Me By Your Name. Hm. At any rate, I realized as I was learning that my arpeggios completely fucking suck. They are incredibly inconsistent both in timing and in volume. And so I set out to build a tool to quantify just how poorly my piano technique had gotten.

I taught piano in high school and college and it had occurred to me that it would be useful to understand ones deficiency and progress in the evenness of fingers with respect to timing and volume. By way of example, it would be nice to know that, on major scales, you hit your thumb 15% louder than the rest of your fingers. And as you turn your fourth finger over in your right hand on the descent of E-Major scales in particular, you lose about a hundredth of a second.

This decomposes into a two subproblems:

How do you detect which hand plays which note?

How do you detect (and must you enumerate) the exercise being played (and the exercises the system supports)?

Once you build these, you essentially just need to map each note in an exercise to the finger it should be played with and voila you have a piano coach. I toyed with the idea of building a arbitrary fingering-annotation model, allowing you to avoid the need to map notes in an exercise, or to enumerate the exercises supported by the system. But to what end? Ultimately, you need a way to communicate back what the user is doing, track their progress, and this isn’t a performance tool as much as it is a practice tool. I could see it being a natural extension of this project but for now, I’m content to specify the exercises this system can analyze, and hardcode mapping of note to finger for each of those exercises.

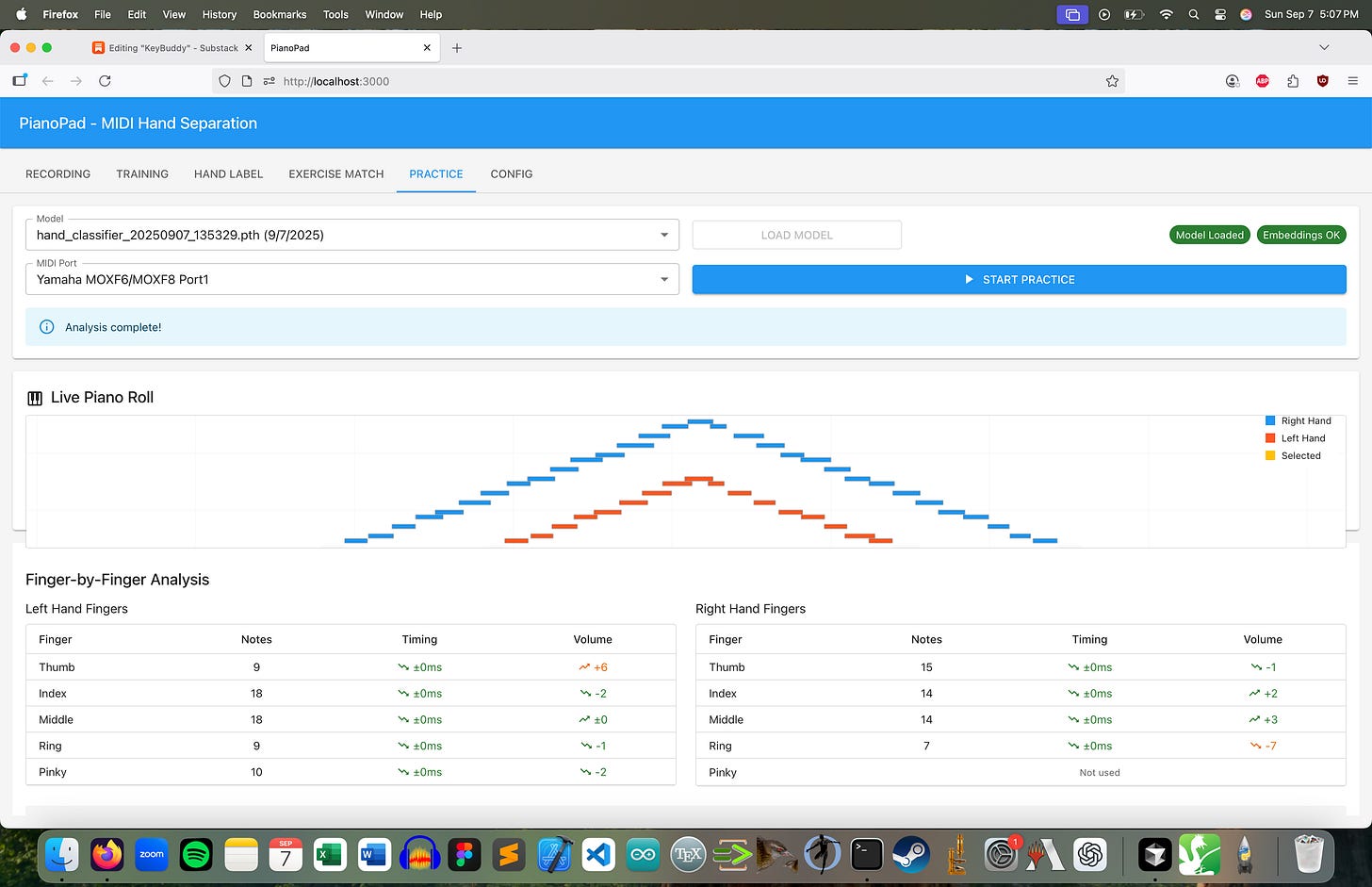

At first blush detecting handedness appears easy. Employing the eye-mediated “isn’t it obvious” algorithm works remarkably well on the input below. Implementing it reveals more nuance. Thresholding rules quickly fall apart in scales beyond an octave. ‘Higher of two simultaneous notes’ breaks when two notes played by the same hand overlap. You could imagine a verbose set of if-else statements to account for missed notes and any number of other maladies that plague my subpar performance of this rudimentary exercise but truthfully it was easier just to train a very small multi-layer perceptron to tackle the job. The input features were the normalized pitch number and time since previous note with a window of 16 notes. Surprisingly, trained only on C and D-major scales, it is robust to minor scales, scales in thirds, and even Hanon. It seems to have learned some representation of ‘you have 2 hands playing the same-ish pattern, the higher of the two is the right hand.’ Impressive! Generally, I think this is the exact type of problem classifiers are good for. Simple to understand but hard to cover the edge cases of.

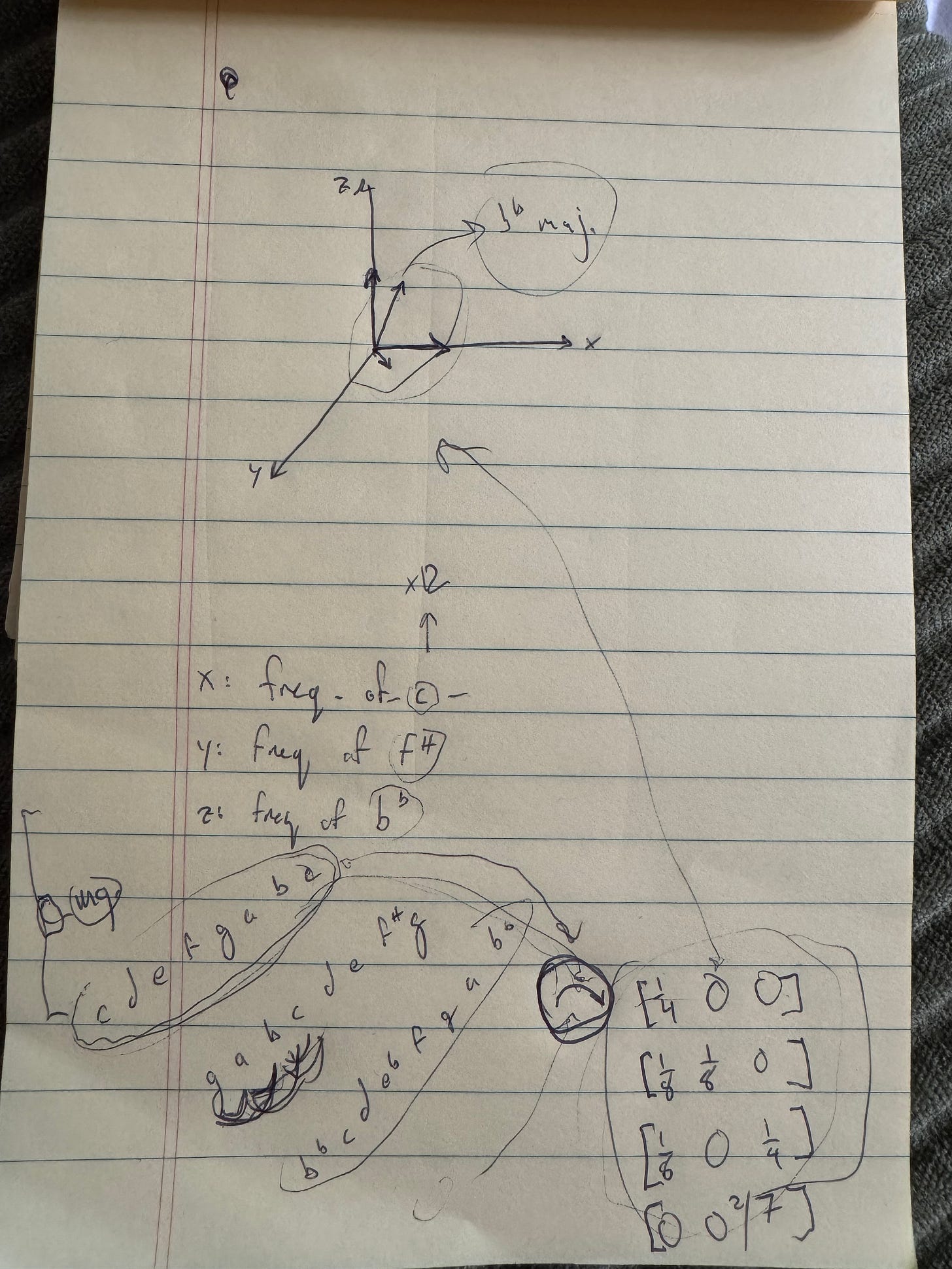

Exercise attribution requried a bit more creativity. It’s arguable that, once I’m already enumerating exercises, I really needen’t detect them at all. But I wanted to so I did. And I’m very happy with the solution. Essentially, I created an embedding model to represent a sequence of notes. Unlike the above, there was no ‘machine learning’ involved. I simply extract features of the input sequence and embed those, and then on an input, similarity search across the exercise space. This works amazingly well. The features are around note and interval frequency, and with relatively few (< 100) exercises, search and embedding is almost instant, even with no vectorDB.

In the above, I explain embedding spaces to my girlfriend as a defensive response to her question “Why aren’t you working on the Ravel?” I demonstrate how my system is robust to dropped notes, as a Bb major scale where the student misses a C, in this toy example, will still resolve correctly as its nearest vector is the correct scale.

Finally, I can test finger-by-finger analysis. In the first run, it correctly detects the exercise and reports that my thumb was 17 ticks louder than my other fingers (exactly what I was going for). The timing analysis said I was perfect so obviously that is broken but it seemed good enough to post.

Unintentionally, I think this highlights the threshold at which software engineers are already automated. I didn’t write a single line of code for this project - it was all Cursor and the entire thing was completed over the course of about 36 hours. If you are a jira-bot engineer you are completely fucked. Coding agents can reliably one-shot well-articulated technical solutions. What they can’t do, is come up with the embedding idea, or guide analysis, or decide on a good input layer for the hand separator (Cursor was instant that velocity was an essential input, it isn’t).

Additionally, it’s a very human trait to know your limits. I come from a mechanics background and in any physical system, the fewer parts you have, the fewer failure points there are, the more robust your product will be. This poblem always seemed daunting when relying on a microphone input but it is made immeasurably easier when using MIDI. Mic-based note transcription is very noisy, with SOTA models achieving only 93% accuracy. This before you account for the diversity of mic qualities and how that might negatively affect note transcription. Any downstream analysis would have suffered from the low quality input.

I think MIDI input is currently the right medium to quantify piano performance in and now I will get back to my arpeggios.

does this mean you’ll learn the Ravel piece now?